As Clifton Harcum began to climb Baker Mountain near Saranac Lake in the Adirondacks, fears entered his thoughts. Climbing the mountain was a new experience for Harcum, who had just started a new job in the area as the program coordinator for the Division of Diversity, Equity and Inclusion at State University of New York Potsdam. He and his family moved to the area in the early stages of the pandemic. He enjoyed jogging and doing trails, but the more he learned about the health problems caused by Covid-19, the more it spurred him to improve his health and get in shape.“I didn't want to get sick. Nobody knew what was going on, “ Harcum says. “And I wanted to make sure I was healthy for my family.”

But as he trekked up Baker Mountain, fears about safety increased. “You think of all kinds of stuff as a Black person in the mountains,” Harcum says. Those fears range from getting hurt to encountering animals, or even encountering other people who might cause harm. With each step, Harcum’s fears grew louder in his mind, preventing him from going forward and prompting him to head back down the mountain. As he retraced his steps, he met a white man going up the mountain who seemed friendly.

Harcum worriedly asked the man, “Do you mind hiking with me?”

The man agreed to go up with him. As they climbed and chatted, they found a common bond in being former athletes and made their way to the top of the summit. But they didn’t talk about George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery, or even Central Park birder Christian Cooper. Harcum avoided those kinds of conversations. He grew up in Baltimore City and says he feels privileged to experience the beauty of the Adirondacks and that it makes him a stronger and better man. He’s hiked more than 40 mountains and more than four hiking challenges and hopes to do more in the future. “I like the challenge, and the serenity, and the peace, and just experiences that a guy from Baltimore City would never have access to,” he says.

Clifton Harcum has hiked in the Adirondacks with his son and has felt the surreal beauty of the area even though he is one of the few people of color that hike in the park. Photo courtesy of Clifton Harcum.

Those same qualities serve as a draw to many who visit the area. Located in the northern rural region of New York state, the Adirondack Region borders the Adirondack Mountains to the south, the Canadian border to the north, Lake Ontario and the Saint Lawrence Seaway to the west, and Lake Champlain to the east. It comprises 6.1 million acres, including more than 10,000 lakes and 30,000 miles of rivers and streams. It includes 12 counties, multiple universities, more than a dozen state correctional facilities, and is home to the largest remaining intact, temperate deciduous forest ecosystem on the entire planet.

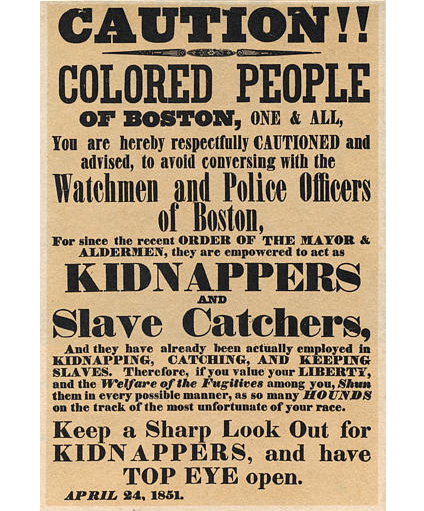

Around the time Harcum scaled Baker Mountain in 2020, the community he and his family joined was wrestling with how to respond to the national reckonings regarding racial inequities, police brutality, and inclusivity in outdoor spaces. About 1 million people reside in the Adirondack Region. About 91% of those identify as white, barely 2% as Black, and less than 1% as every other race or ethnicity. Visitors and residents of color have long shared anecdotes of racist encounters, including one involving Aaron Mair, an Adirondack resident and the first Black president of the Sierra Club. The area also earned press for a town’s refusal to allow a street painting spelling out “Black Lives Matter” on the pavement.

But residents of the Adirondacks such as Pete Nelson also have witnessed people working to make this area more welcoming to people of color. Nelson, an educator, activist, and co-founder of the Adirondack Diversity Initiative, has worked to illuminate the socioeconomic and racial diversity issues in the Adirondacks. In 2015, he helped co-found the Adirondack Diversity Initiative, a volunteer-run coalition of organizations and individuals who develop and promote strategies to help the Adirondack Park become more welcoming and inclusive for all New Yorkers. In May 2019, New York State announced that $250,000 of its 2020 budget would go to the ADI as part of the $300 million Environmental Protection Fund. This allowed the hiring of a new director and the expansion of its initiatives and outreach efforts.